Apple II Hardware Review

The following is a review of the original Apple II microcomputer.

It appeared in the Jul-Aug 1978 issue of Creative Computing. The magazine is no

longer published so the address in the following notice is invalid but I'm

including the notice per the instructions in the magazine on re-printing their

articles:

Copyright © 1978 Creative Computing

51 Dumont Place,

Morristown, NJ 07960

A Creative Computing Equipment

Profile...

Apple II Computer

Steve North

With the state-of-the-art advancing so rapidly, many prospective

micro buyers are looking for much more than a box with a CPU and some memory.

All-in-one machines like the TRS-80 and PET, oriented towards computer

users, not builders, are far outselling the older-style machines. In

this exploding market for completely assembled consumer computers, the Apple II

has some impressive features unmatched by many other micros.

The Apple II is based on the 6502 microprocessor, which has a

number of devoted users (the 6502 is used in the PET, too). The Apple features

a built-in ASCIl keyboard, cassette interface, and a video interface, which is

its most outstanding feature. The memory-mapped video interface displays both

color graphics and normal alphanumeric data. The video interface may be

connected to a color monitor. or to a regular color TV with an RF modulator.

(M&R Enterprises makes such a modulator, which fits right inside the Apple

and which requires absolutely no soldering. This is what we're using at

Creative.) All the Apple's circuitry is contained on a single

printed-circuit board that fits along the bottom of the Apple cabinet. Sockets

are provided for extra memory (up to 48K of RAM) and extra I/0 cards. 16K of

memory is a reasonable amount to start with. The Apple also comes with two

"game paddles" which are either one dimensional joysticks, or knobs. Each game

paddle also has a push button switch. (Two more game paddles may be

accommodated by the Apple but they are not provided with the standard unit.) To

provide sound effects for games, primitive music synthesis. or just an audible

signal, the Apple has a small built-in speaker under computer control. These

peripherals are quite handy for many video games.

Built-In Software

The Apple II's built-in software (in ROM) includes a system

monitor program, which is entered whenever the RESET key on the keyboard is

pressed. This monitor lets you interact with the machine at a low level: read

or save memory images on cassette tape, examine and change memory and CPU

registers, go to a user program, etc. The monitor program also includes a

"mini-assembler" which permits entry of machine-language programs by specifying

a mnemonic and then the operands in hex. Better than nothing, I suppose, but

not nearly as handy as a real assembler. The system monitor also has a built-in

16-bit processor simulator, called SWEET-16. This program, written in 6502

machine language, executes programs written in the language of a simple

hypothetical 16-bit processor. Programs simulated this way are obviously a lot

slower than they would be running on a real machine, but for some programming

SWEET-16 can be used to write shorter and faster code.

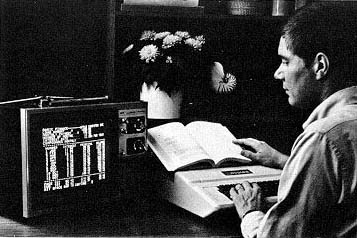

The compact Apple II computer comes with a pair of game

paddles and built-in integer BASIC. Among the many software options are

Applesoft floating-point BASIC and the preprogrammed Checkbook.

Integer BASIC

Most Apple users will be more interested in the Apple's built-in

integer BASIC. To enter BASIC from the monitor, just type control-B. Integer

BASIC is quite complete and includes functions to access the color graphics,

game paddles, etc. It doesn't have floating-point math, but it turns out that

you can do a lot of things without floating point, especially in the area of

graphics, where speed of execution is often a critical factor (hence the

speedier integer math is in some ways desirable!).

Apple's integer BASIC does allow character strings, multiple

statements, PEEK, POKE, CALL (for interfacing to assembly-language code), a

TRACE mode, and other advanced features. Variable names are not limited to one

or two characters, so they can be assigned to suggest the data they represent

(for instance, RADIUS means a lot more than R1 when reading a BASIC program).

Only the first two letters of a variable name are considered significant by

BASIC, though.

The game paddles are accessed by the PDL function. PDL(O), for

instance, returns a value from 0 to 255 representing the position of game

paddle #O. The GR statement tells the Apple to enable the graphics mode. In

this mode, most of the display is reserved for color graphics, but the bottom

three lines are used to display alphanumeric output (such as the execution of

BASIC PRINT statements, INPUT. etc.). Furthermore, these two areas of the

screen operate completely independently of each other - the normal scrolling of

the bottom three lines of text does not affect the graphics area. I prefer this

to the TRS-80's graphics, which force you to mix graphics and alphanumeric

output on the same screen, so if the text has to scroll, so do the graphics.

Before actually using the graphics, a COLOR statement is executed. This tells

the Apple what color you want to plot in next. COLOR=9, for instance, means

that you want to plot in orange. The colors are numbered from 0 to 15. If you

don't want to use numbers, just say ORANGE=9 at the start of your program, and

thereafter you can say COLOR=ORANGE. The COLOR statement doesn't restrict the

display to one color; it's just that you plot graphics in only one color at a

time. Once the color is set, you can draw some pictures The screen is broken up

into a 40x48 grid. PLOT X,Y will plot a particular point on the screen, while

HLIN Y1,Y2 -AT X1 and VLIN X1,X2 AT Y1 are used to draw horizontal and vertical

lines. The SCRN function is used to examine the color plotted at any square on

the screen. 40x48 graphics sound somewhat crude, but they're actually pretty

good and are suitable for many nifty games, like Breakout (which comes with the

Apple). And all this is available at the flick of a switch. (BASIC programs, of

course, must be loaded from cassette).

Graphics Software

If you want more programming power, Apple has some other software

products of interest. One of these is HIRES, a high-resolution graphics

package, that permits plotting on a l60x280 grid, but only four colors (black,

green, violet, and white) are allowed. You tell HIRES what to draw by POKE-ing

parameters into fixed locations in memory. The HIRES routines can be used to

plot a single point, a line, or a shape. To plot a shape, you have to set up a

table of vectors which, given a starting location, tell the computer how to

draw the shape. These vectors must be encoded in a binary notation that

requires a little practice. HIRES is not only able to draw the shape, but also

accepts a scaling factor (1 is normal size, 2 means twice normal, up to 255)

and a rotation factor (0 means normal, 16 means rotate the shape 90 degrees,

and so on). The HIRES package can be read from cassette tape, or put in a ROM

if you use it frequently. 8K of memory must be reserved for the graphics

alone.

Users of Apple II can choose among a variety of

preprogrammed software including Basic Finance, Checkbook, and High-Resolution

Graphics.

Floating-Point BASIC

Applesoft BASIC is a full-feature floating-point BASIC, also

loaded from cassette. You need at least 16K of memory to use it. Applesoft is a

version of the popular Microsoft BASIC, with some special features for the

Apple's graphics, generally very similar to those in integer BAS IC. Applesoft

does not have PDL functions, so to access to paddles, you need to use the PEEK

function to read the paddle input port. Most Apple owners will probably want to

use the Applesoft BASIC for serious application programs and more complex BASIC

games, and integer BASIC for video games and simpler BASIC programming.

Documentation

The Apple documentation is variable, but more often than not,

excellent. The integer BASIC manual, by Jeff Raskin, is outstanding. An

absolute novice could pick up this book and begin using his Apple immediately,

yet an experienced computer user won't find it frustrating. The Applesoft

manual is rather skimpy. but it's intended as a short reference, not a text on

BASIC. Nevertheless, there are a few BASIC example programs. A third manual, on

the Apple itself (doubtless the first manual Apple had) attempts to cover

everything - setting up the Apple, demo programs, integer BASIC, the system

monitor, and the hardware including schematic diagrams. Actually, it isn't that

bad, but it falls short in some important areas. For instance, the

documentation on SWEET-16 consists of nothing but an assembly listing. I

wouldn't even have known what the thing is, except that Steve Wozniak of Apple

wrote an article for Byte on SWEET-16. At least they could get reprints.

The documentation on HIRES was also a bit confused (the really intricate

details on encoding the shape vectors were written by hand, yet). Obviously,

Apple is in a transition phase with its documentation, and they've started with

the documentation most important to new users. People who want to get into the

system software are better equipped to piece out what's going on for

themselves, and hopefully Apple will shortly bring the rest of the

documentation up to the high standards of the BASIC manual.

The Apple II computer is a one-of-a kind machine, probably the

best micro on the market for color graphics. I also like the Compucolor

machine, which has really superb color graphics and a light pen. but it's a

little beyond my budget, and probably of many other consumer computer buyers.

whereas the Apple is quite reasonably priced. There were a couple of things I

didn't like about the Apple, too. The cassette interface did not like my

cassette recorder, but I hear it works fine with Panasonic recorders. I would

guess that the cassette works at 1200 baud, which is reasonably fast. The

display is upper-case only, a throwback to the olden-daze of computers, but

perhaps Apple had a reason for this. The display is rather narrow (40

characters) but you can compose lines longer than this by just typing past the

edge of the line; the computer knows that it has to continue on the next line.

Also, in integer BASIC, there is no way to slow down the listing of a program -

it just keeps flying by. You can either list within a given range of line

numbers just enough to fill the screen, or else hit RESET in the middle of a

list, in which case you're back in the system monitor and have to type two more

keystrokes to get back into BASIC with the program intact. One other complaint:

the keyboard has cursor-right and cursor-left keys, which are very helpful in

text editing with the screen, but no cursor-up, cursor-down, or home keys.

Instead an "escape sequence" (the escape key and then another key) must be used

to perform these functions. Also, the operation of the Repeat key is rather

erratic: it should only operate when another key is depressed but sometimes

pressing Repeat by itself causes the previous character typed to be echoed

again. These are not really major problems, though.

Options

Options for the Apple II, besides more memory (all you need to

expand the memory are a handful of ICs, which were called "Appleseeds" in one

advertisement I saw) include interfaces for a printer, modem, and floppy disk.

All of these are quite handy. The printer can be used to provide hard copy of

BASIC programs or other stuff. The communications interface, used to connect a

modem, would indicate that Apple sees networking of microcomputers as an

important thing in the future. but to accomplish this a lot more will be

required than hardware. It's a start. anyway. The floppy-disk option should

also be interesting, since anyone who has used floppies can tell you they have

it all over cassettes. It should be interesting to see whether floppy-disk

attachments for computers like the Apple and TRS-80 enhance or detract from the

integrated structure of hardware and software of these systems.

In short, the Apple is certainly one of the most versatile micros

on the market. The user can view it as either a very sophisticated video game.

a BASIC-speaking graphics machine, or a real nuts-and-bolts

computer-computer. The Apple is not a machine for the classroom, or for

the hobbyist who wants to use all the nifty S-100 boards, but for those

especially interested in using a computer, even if they're just

beginners, the Apple II is an excellent choice.

|